Now that you understand story beats, we’re ready to design something to put the engine of your mystery novel inside. And that thing we’re putting it in is… a house! (No, not a car. Plot twist!)

This house will be built out of the sixteen story beats you learned about in the last chapter. And, just like an architect doesn’t draw the blueprint for a new house from right to left, you’re not going to be inking in your story beats from first to last. Rather, you’re going to be deciding on them in a very specific order—an order than lets you build up your story in a natural, intuitive way.

Let’s go back to that architect and imagine what he does when he first sits down in front of his drafting table, ready to take all of the airy ideas in his head and commit them to paper. He starts by sketching in the most important rooms first—the entry hall, the kitchen, the living room—the large rooms that give the house its structure and its unique character.

Just so with you. You’ll start by creating the important high points and low points of your story—the beats that give it its structure and unique character. These beats are:

Inciting Incident

The Challenge Accepted

The Midpoint

Go the Hard Road

The Confrontation

After that, the architect starts filling in some of the other rooms—the bedrooms, the baths—areas that still add a great deal to the overall experience of the house, but aren’t quite as foundational to the floorpan. You’ll do the same, adding in the beats that comprise your Sleuth’s investigation, as well as a major defeat she suffers along the way:

A Grave Setback

Down & Out

Investigation #1—Getting Curious

Investigation #2—On the Case

Investigation #3—Things Fall Apart

Investigation #4—Final Clues

Finally, the architect is going to fill in the details. He’ll give his house closets, light switches, and an HVAC system. The potential homebuyer isn’t going to waste a lot of time thinking about these necessities—but she sure will miss them if they’re not there. Here’s where you’ll firm up the beginning and ending of your novel, by addressing these beats:

Opening Scene

Opening Status

Loose Ends

Celebrate Sleuth’s Changed Status

The Story Continues (optional)

The First Two Beats

In the rest of this chapter, we’ll be talking about how to write just two beats: The Challenge Accepted, and The Midpoint.

The reason we’re starting here is that one of these beats should probably be your murder. These are the two natural places the murder belongs:

near the beginning—to get the ball rolling

smack in the middle—to deliver a mid-book shake up

The first option, a murder near the beginning, is by far the more common—especially in modern novels. That may have something to do with the rushed, distracted, competitive nature of modern life. Writers often feel a need to hook readers right from the get-go—and agents and publishers frequently share this perspective. From a publishing standpoint, an early murder may be your best bet if you’re trying to land a contract for your first novel.

However, from a structural standpoint, the Midpoint murder works perfectly, and you’ll see it in plenty of older novels—even those from just a couple of decades ago. So even if you want a big, splashy page-one murder to anchor your series and secure your publishing contract, keep the Midpoint murder in your back pocket. You may find a use for it in a later volume.

Murder at the Midpoint

When your book has a Midpoint murder, the first half of the novel will be spent exploring the tensions that exist among the community of characters. We’ll flesh out conflicts, expose secrets, and make motives clear. Then, at the Midpoint, these simmering tensions will erupt into murder.

To figure out the best Inciting Incident for your book, let’s review a concept we discussed earlier: the Villain’s Trigger—the event that causes him to commit murder. Remember that Triggers generally involve:

The Villain being put under pressure—financial, romantic, or otherwise

The Villain becoming aware of a new opportunity to profit by murder

Gatherings serve as wonderful opportunities for your Villain to experience both kinds of Trigger.

At a gathering of old college chums, your Villain may realize that his wife is having an affair with one of their friends—putting him under romantic pressure, and prompting him to commit a Love murder.

At an academic conference, your Villain may realize he has an opportunity to pass a colleague’s work off as his own—so long as he kills the colleague first.

At a family reunion, your Villain may experience an opportunity to get away with murder—since, for the first time in years, he’s sharing space with both his intended Victim, and the person he intends to frame.

So, ask yourself: what is your Villain’s Trigger? If it takes place at a gathering, that gathering is likely the best Inciting Incident for your novel. In addition to providing a backdrop for the Trigger, it will add some drama and pageantry to your opening chapters, and allow you to fill them with a bevy of colorful suspects.

But what if the Trigger isn’t a gathering? In that case, your Inciting Incident is likely a minor crime, or other troubling disruption to the Sleuth’s social order. Maybe:

She receives a threatening letter in the mail

She learns her sister’s boyfriend isn’t who he appears to be

Her elderly neighbor comes to her for help when his cat goes missing

Whatever the minor crime that occurs, looking into it will lead your Sleuth down the rabbit hole, learning more and more about the Villain’s actions—and becoming more and more invested along the way. By the time the murder occurs at the Midpoint, your Sleuth will already be fully committed to unraveling this plot.

Let’s take, for example, that missing cat. Perhaps the Villain has been researching a long-ago bank robbery, in which the money was never recovered. He believes that the robbers hid the money in the home now owned by the elderly neighbor. He broke in to search—and inadvertently let the cat out.

Your Sleuth will uncover traces of the break-in, and begin to unravel the story of the bank robbery. Every step she takes makes her more intrigued, and more determined to figure out where the treasure is—and who is after it. When she finally drills into the floor of her neighbor’s basement, she’ll find no fortune—but a skeleton instead! She’ll be bound and determined to not only solve this long-ago crime, but also to learn who is after the fortune in the present day.

Examples of Midpoint Murders in fiction: Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie; Die for Love by Elizabeth Peters; Gosford Park

Murder at the Start

But what if you want a murder right at the start? Well, it’s still important to know what your Villain’s Trigger is, and whether it takes place at a gathering.

If it does, then your Inciting Incident is probably a longish sequence—perhaps two to five scenes—that begins with the gathering, and ends with the murder. This clears the way for your body to drop by the end of Chapter 3, securing the interest of those impatient readers.

And if the Trigger doesn’t take place at a gathering? Then the Inciting Incident is most likely the murder itself.

In either case, the ideal Midpoint for your novel will probably be the deployment of a Midpoint Plot Twist—something that sends the Sleuth’s investigation rocketing off in a new direction for the second half of the novel. If you don’t have a twist to deploy at this point, you can consider other major changes that will drastically affect your Sleuth’s circumstances, such as the loss or addition of an ally.

Your Scene Index

Do you have an idea of what will occur during your Inciting Incident and Midpoint? If so, it’s time to begin creating your Scene Index—a simple list of every scene that will occur in your book.

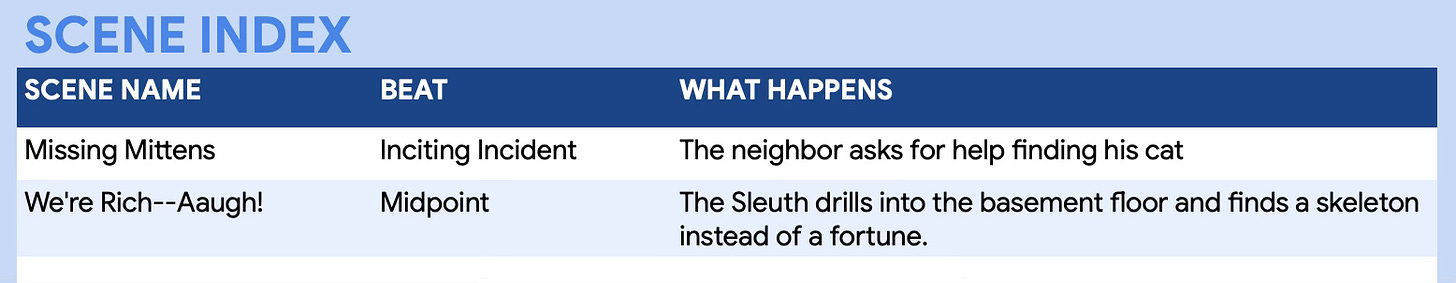

My Scene Index, you won’t be surprised to learn, comes in spreadsheet form. For each scene, I note down what beat the scene is meant to fulfill, and a brief description of what happens. I also like to give my scenes funny names, so at this point my Scene Index for the novel with the missing cat might look like this:

Later on, I’ll add a couple of columns to this spreadsheet: one for keeping track of any clues that need to be dropped in this scene, and one for noting the approximate time it happens, such as “Monday morning” or “Wednesday night.” But right now, as with everything else in The Perfect Crime system, we are keeping our Scene Index lightweight. We don’t want to invest a great deal of time in hammering down the details when changes may still occur.

These two beats are the most important structural pins to get into place, so you can start seeing the shape of your novel. Next week, we’re going farther, by nailing down three critical beats that will force your Sleuth to come face to face with her Chronic Issue. We’re talking about The Challenge Accepted, Go the Hard Road, and The Confrontation.