Ch. 17: Alibis & Ch. 18: Locked Room Murders

Chapter 16: The Four Types of Alibi; Chapter 17: My Favorite Plot Twist (Time-Shifting!)

This post contains Chapters 16 and 17 of The Perfect Crime, my mystery-writing textbook. To read previous chapters, check out the Archive.

Chapter 17: The Four Types of Alibi

In this section of the book, we’re going to talk about perfect alibi crimes—crimes in which your Villain seems to have an unimpeachable alibi, which your Sleuth must break. There are four kinds of alibis your Villain can use to craft the illusion of his innocence. In this brief chapter, we’ll describe those four alibis—and in the following chapters, we’ll discuss how each can be broken.

The Occupied Alibi

This is the kind of alibi you’re probably used to thinking of when you hear the word “alibi.” The Occupied Alibi is a story that describes where the Villain was at the exact time of the crime—performing in the opera, say, or hearing confessions at church.

We call it an Occupied Alibi because the Villain seemed to be otherwise occupied at the time of the crime. But we can think of alibis more broadly as any circumstance that makes it impossible for a particular person to commit a crime. Such as:

The Distance Alibi

In this alibi type, the Villain is unable to account for his whereabouts at the exact time of the crime. However, he establishes his whereabouts very close to the time of the crime—in a location too far distant for him to travel the intervening distance. Perhaps he establishes that he was in New York mere minutes before (or after) the crime occurred in Paris.

The No Access Alibi

In this alibi type, the Villain doesn’t worry about establishing his own whereabouts. Rather, he works to establish the Victim’s whereabouts—in a location to which the Villain supposedly had no access.

This alibi type really shines in Locked Room Murders. If your Victim was killed while alone in his locked study, a No Access Alibi is what your Villain has. However, it can also be used in any story where the Victim is in a location that seems inaccessible—such as a walled estate from which the Villain has been barred.

The Incompetence Alibi

Location doesn’t matter to this alibi type. Instead of establishing whereabouts, the Villain works to establish that he was incapable of committing the crime—often physically incapable, though a mental incapacity could work as well. These crimes often involve a mismatch between the skills needed to commit the crime, and the supposed abilities of the Villain. For example, your Villain might shoot your Victim with a bow and arrow—despite supposedly being blind.

These are the four types of alibis used in mystery fiction—and there are ways your Sleuth can break all of them. In the next several chapters, we’ll dig into this subject, starting with a very special kind of perfect alibi mystery—the Locked Room Murder.

Chapter 18: Locked Room Murders

The No Access Alibi, and How to Break It

One delightful type of perfect alibi plot is the Locked Room Murder. In this type of mystery, your Villain has a No Access Alibi, because (it appears) the Victim died while alone in a locked room.

Before we go any further, let’s talk about what a locked room actually is. It doesn’t, strictly, have to be a room, nor does it truly have to be locked. We’re going to define a locked room as any area that no one can enter or leave without being seen. Once we apply this definition, we can see that all of the following would qualify as locked rooms:

an airplane in flight

a train car

a blind alley with a security camera focused on the open end

A “locked room” is an area that no one can enter or leave without being seen.

People may be able to leave or enter some of these areas. But not without being seen—that’s the core element that transforms any area into a locked room, because it means that the characters can be reasonably sure they know who does, and doesn’t, have a No Access alibi.

In a Locked Room Murder, the Victim dies while in a locked room, either alone, or with one other person—the Patsy, who is innocent, but looks extremely guilty due to his location.

There are really only a handful of possible solutions to Locked Room Murders, and in this chapter, we’re going to go over all of them.

Time-Shifted Murder

In an episode of Monk called “Mr. Monk Goes to the Carnival,” a police officer and an informant meet at the carnival to discuss an upcoming drug deal. The informant says he wants a guarantee of privacy, so he’ll only talk on the Ferris wheel. The men board the ride together, and now their car becomes our locked room. No one can enter or leave it without being seen.

As soon as the ride gets underway, the informant starts screaming and thrashing around. “He’s trying to kill me!” he yells. The ride operator stops the ride, and the police officer bounds out of it, eager to get away from this crazy informant. But he’s quickly called back. The informant has been stabbed.

The officer insists that he never hurt the informant. So what happened—and why? Well, our Villain is a drug dealer who wanted the officer smeared as a violent cop, so that his testimony in an upcoming case would be discredited. The Villain paid the informant to pretend to be attacked. But the informant didn’t know the plan was going to culminate with him being stabbed—by the Villain’s accomplice, the ride operator. As soon as she opened the car, and the officer staggered away, she darted in and killed the informant. Then she screamed, as though she had discovered, rather than inflicted, his wounds.

This is a Time-Shifted Murder, and over the course of the next few chapters, we’re going to see how time-shifting is a fantastic way to break not just a No Access alibi, but most of the alibi types. When we time-shift an event, we change the characters’ perceptions of when it took place. In this case, the stabbing took place after the locked room was opened—that is, after it became accessible to other people. But it was time-shifted so that it seemed to happen while the room was locked.

When we time-shift an event, we change the characters’ perceptions of when it took place.

Before we move on, let’s look at one more Time-Shifted Murder.

In an episode of Monk called “Mr. Monk Goes to the Theater,” Adrian Monk is attending a play in which his assistant’s sister, Gail, is starring. During a big scene, Gail’s character is threatened by her abusive husband, and stabs him in desperation. This all goes according to the script—but after Gail stabs her co-star with the stage knife, he collapses, obviously in true physical pain.

A cast member calls out for a doctor in the house, and a man rushes forward to examine the fallen actor. When he declares the man dead, Gail looks very guilty indeed.

But she insists she’s innocent, so what happened? Well, the man did experience a medical emergency on stage—but not as a result of Gail’s actions. Instead, the distress he was feeling was the result of an allergic reaction to peanut oil that the Villain—Gail’s understudy, who wants Gail’s part for herself—had used to sabotage one of the props. When the cast called for a doctor, the man who answered wasn’t a real doctor—he was the Villain’s accomplice—her father, who is as obsessed with her career as she is. He rushed onto stage, and while pretending to treat the Victim, actually removed Gail’s stage knife and stabbed the man with a real knife, killing him.

We’ll talk (much!) more about tactics for time-shifting over the next few chapters, but both of these episodes use the same tactic: a false attack. A false attack is a moment when characters believe the murder is taking place. In the case of “Mr. Monk and the Carnival,” the false attack occurs when the informant begins screaming. And in “Mr. Monk Goes to the Theater,” the false attack occurs when Gail’s co-star collpases. They’re different events, but both convince onlookers that the exact time of the murder is known.

A false attack is a moment when characters believe the murder is taking place.

There are a few other solutions to Locked Room Murders that we want to look at, but first let’s talk about what “Mr. Monk Goes to the Carnival” and “Mr. Monk Goes to the Theater” have in common—which is, from a structural standpoint, everything.

In each episode, the basic plot plays out the exact same way:

The Victim enters a locked room with the Patsy. (The officer and informant go up in their Ferris wheel car, and Gail’s scene with her co-star begins.)

A false attack occurs. (The informant screams for help, and the co-star collapses.)

The locked room is opened. (The Ferris wheel stops, and people begin to enter the stage.)

One of the people who opened the locked room kills the Victim. (The ride operator stabs the informant, and the fake doctor stabs the actor.)

I want to emphasize the similarity of these plots not to criticize Monk, but to make it clear that these solutions we’re discussing in this chapter are structures only. There is nothing wrong—either legally, or morally—with using them as jumping off points to craft your own plot. Your plot will have a locked room of your own devising, it may have a novel form of false attack, and it will certainly be peopled with characters who are entirely your own.

Gains Access Murders

In an episode of Monk called “Mr. Monk and the Panic Room,” record executive Ian Blackburn gets an alert from his security system—there’s an intruder on his large estate. He picks up his pet chimp, Darwin, and the two of them seal themselves inside a panic room. When the police arrive the next day and open the door, Ian is dead. And Darwin is holding the gun.

So, poor Darwin is the Patsy, and is in danger of being put down, until Monk figures out who actually killed Ian. Our Villain is the man who installed the panic room in the first place. He build a secret entrance into the back of the room’s refrigerator, with the intention of sneaking in and killing Ian, so that he could be with Ian’s wife.

This is a Gained Access murder, in which the Villain enters the locked room by some sort of clever means. To write this kind of plot, it won’t do to simply give your Villain a spare key—he must have some clever, unexpected means of entering the room. And an entrance through the back of the fridge in a panic room definitely fits the bill.

Extra People Murders

In an episode of Murder, She Wrote called “Off to See the Wizard,” theme park magnate Horatio Baldwin is working late when the building’s security guards hear a gunshot from inside his office. They try to respond, but the door has been bolted from the inside. They call Baldwin’s second-in-command, Phillip Carlson, for instructions, and he tells them to break down the door. When they do, they find Baldwin dead at his desk, and no one else in sight.

The police arrive and examine the room, but one thing is clear—no one gained access to the room, which is in the basement and surrounded by rock on three sides. Nor does a time-shifted murder seem likely—the two security guards entered the room together, making it unlikely that one of them could have offed Baldwin without the other noticing.

So what happened? Well, Phillip Carlson is our Villain. He accidentally killed Baldwin early in the evening, then came up with a plan to conceal his guilt. He went to his own office, and set up his phone to forward to Baldwin’s. Then he locked himself inside with the body, disconnected the bell on Baldwin’s phone so that it couldn’t be heard ringing, and fired the gun into the dead man’s temple. When the security guards called Carlson for instructions, their call was forwarded to Baldwin’s office, where Carlson picked it up. He told them to break down the door, then hid behind a large piece of furniture. When the guards entered, they immediately went to inspect the body, giving Carlson the brief window he needed to sneak out of the room, and pretend that he had been in his own office all along.

This is what I call an extra people murder, because there are extra people in the locked room who are overlooked for one reason or another. Maybe they’re concealed, like the villain in this episode, or maybe they seem to be incapable of committing the murder due to age, infirmity, or some other disqualifying factor.

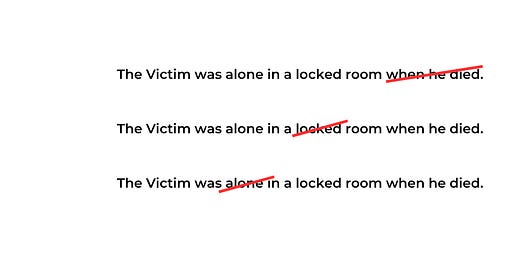

Remember that a plot twist is something the reader believes that turns out to be false—and in a Locked Room Murder, the belief is generally this: “The Victim was alone in a locked room when he died.”

Each of the three solutions we’ve discussed violates this belief in a different way. Let’s take a look.

For Time-Shifted Murders, we can strike through the words “when he died.” The Victim might have indeed been in a locked room, but only before, or after, his death took place.

For Gains Access Murders, we can strike through the word “locked,” because the room wasn't as locked, or inaccessible, as it appeared to be.

And for Extra People Murders, we can strike through the word “alone—” because the Villain was with him.

But hold on, because there are two more forms of Locked Room Murders that actually allow the sentence, “The Victim was alone in a locked room when he died” to stand, intact.

It Wasn’t Murder

At last we have reached the part of the book where I simply can’t find any example plot to show you! Nevertheless, I feel duty-bound to mention the fact that it would be entirely possible for a Locked Room Murder to be the result of suicide. This would be a Victim Did It twist (covered in detail in Chapter 11), in which the Victim/Villain set up his suicide to look like murder.

Perhaps the reason I don’t have an example is that such a plot seems, at least at first blush, a bit disjointed—if you want to make your suicide look like murder, why commit it in a locked room? But the possibilities are intriguing. Perhaps your character wants to frame a Patsy who’s in the locked room with her, or perhaps she simply doesn’t realize that her room has become locked.

Exterior Forces Murders

In an episode of Monk called “Mr. Monk Meets the Playboy,” the CFO of a raunchy men’s magazine tells its publisher that they’re going to have to shut down production. The next day, he’s working out alone in his office when a heavy weight crashes down onto his neck, killing him.

This is a case where there’s no time-shifting, no gained access, and no extra people. But Monk is certain that Dexter Larson, the magazine publisher, is guilty. So, how did he do it?

Well, before Dexter was a playboy, he was a bit of a tech geek. He built a super powerful electromagnet, and entered the apartment below the Victim’s office. Then he used the magnet to pull the bar onto the other man’s neck.

While it’s easy to think of different ways you might use the Time-Shifted, Gains Access, and Extra People structures, it’s a lot harder to imagine possible Exterior Forces murders. The use of magnetism feels quite unique, and isn’t something that can be easily duplicated without feeling a touch reminiscent of this episode. However, it’s important for us to remember that it’s possible to think outside of the locked room.

Locked Room Murders are great fun, but, as we’ll see in the next few chapters, they’re not the only Perfect Alibi plots you can write. In the next chapter, we’ll talk about the Distance Alibi—how your Villain sets it up, and how your Sleuth can break it.

Thanks, Jane, I'm loving this series! Thanks!!

By the way, the subheader says "Chapter 16: The Four Types of Alibi; Chapter 17: My Favorite Plot Twist (Time-Shifting!)" and below it "This post contains Chapters 16 and 17 of The Perfect Crime, my mystery-writing textbook. To read previous chapters, check out the Archive," however, this post is actually for chapters 17 and 18. Not sure if it matters.